Friday, 6 July 2012

Tuesday, 19 June 2012

(EN) The Joyful Side of Translation

The Joyful Side of Translation

By ADAM THIRLWELL

The theory of translation is very rarely — how to put this? — comical.

Its mode is elegy, and severe admonishment. In the 20th century, its

great figures were Vladimir Nabokov, in exile from Soviet Russia,

attacking libertines like Robert Lowell for their infidelities to the

literal sense; or Walter Benjamin, Jewish in a proto-Nazi Berlin,

describing the Task of the Translator as an impossible ideal of

exegesis. You can never, so runs the elegiac argument, precisely

reproduce a line of poetry in another language. Poetry! You can hardly

even translate “maman.” . . . And this elegiac argument has its elegiac

myth: the Tower of Babel, where the world’s multiplicity of languages is

seen as mankind’s punishment — condemned to the howlers, the faux amis, the foreign menu apps. Whereas the ideal linguistic state would be the lost universal language of Eden.

It’s rarely flippant, or joyful — the theory of translation.

David Bellos’s new book on translation at first sidesteps this

philosophy. He describes the dragomans of Ottoman Turkey, the invention

of simultaneous translation at the Nuremberg trials, news wires, the

speech bubbles of Astérix, Bergman subtitles. . . . He offers an

anthropology of translation acts. But through this anthropology a much

grander project emerges. The old theories were elegiac, stately; they

were very much severe. Bellos is practical, and sprightly. He is

unseduced by elegy. And this is because he is on to something new.

Bellos is a professor of French and comparative literature at Princeton

University, and also the director of the Program in Translation and

Intercultural Communication there (at which, I should add, I once

spoke). But to me he’s more interesting as the translator of two

peculiarly great and problematic novelists: the Frenchman Georges Perec,

whose work is characterized by a manic concern for form, and the

Albanian Ismail Kadare, whose work Bellos translates not from the

original Albanian, but from French translations supervised by Kadare.

Bellos’s twin experience with these novelists is, I think, at the root

of his new book, for these experiences with translation prove two

things: It’s still possible to find adequate equivalents for even

manically formal prose; and it’s also possible to find such equivalents

via a language that is not a work’s original. Whereas according to the

sad and orthodox theories of translation, neither of these truths should

be true.

At one point, Bellos quotes with rightful pride a small instance of his

own inventiveness. In Perec’s novel “Life: A User’s Manual,” a character

walks through a Parisian arcade, stopping to look at the “humorous

visiting cards in a joke-shop window.” In Perec’s original French, one

of these cards is: “Adolf Hitler/Fourreur.” A fourreur is a furrier, but

Perec’s joke-shop joke is that it also resembles the French

pronunciation of Führer. So Bellos, in his English version, rightly

translates “fourreur” not as “furrier,” but like this: “Adolf

Hitler/German Lieder.” Bellos’s new multiphonic pun is a travesty, no

doubt about it — and it’s also the most precise translation possible.

The conclusions that this paradox demands are, let’s say, bewildering

for the old-fashioned reader. We’re used to thinking that each person

speaks an individual language — his mother tongue — and that this mother

tongue is a discrete entity, with a vocabulary manipulated by a fixed

grammar. But this picture, Bellos argues, doesn’t match the everyday

shifts of our multiple languages, nor the mess of our language use.

Bellos’s deep philosophical enemy is what he calls “nomenclaturism,”

“the notion that words are essentially names” — a notion that has been

magnified in our modern era of writing: a conspiracy of lexicographers.

It annoys him because this misconception is often used to support the

idea that translation is impossible, since all languages largely consist

of words with no single comprehensive equivalent in other languages.

But, Bellos writes: “A simple term such as ‘head,’ for example, can’t be

counted as the ‘name’ of any particular thing. It figures in all kinds

of expressions.” And while no single word in French, say, will cover all

the connotations of the word “head,” its meaning “in any particular

usage can easily be represented in another language.”

The misconception, however, has a very long history. Ever since St.

Jerome translated the Bible into Latin, discussion of translation has

dissolved into the ineffable — the famous idea that each language

creates an essentially different mental world, and so all translations

are doomed to philosophical inadequacy. In Bellos’s new proposal,

translation instead “presupposes . . . the irrelevance of the ineffable

to acts of communication.” Zigzagging through case studies of missionary

Bibles or cold war language machines, Bellos calmly removes this old

idea of the ineffable, and its unfortunate effects.

It’s often said, for instance, that a translation can’t ever be an

adequate substitute for the original. But a translation, Bellos writes,

isn’t trying to be the same as the original, but to be like it. Which is

why the usual conceptual duo of translation — fidelity, and the literal

— is too clumsy. These ideas just derive from the misplaced anxiety

that a translation is trying to be a substitute. Adolf Hitler/Fourreur! A

translation into English as “furrier” would be literally accurate; it

would, however, be an inadequate likeness.

In literature, there’s a related subset of this anxiety: the idea that

style — since it establishes such an intricate relationship between form

and content — makes a work of art untranslatable. But again, this

melancholy is melodramatic. It will always be possible in a translation

to find new relationships between sound and sense that are equivalently

interesting, if not phonetically identical. Style, like a joke, just

needs the talented discovery of equivalents. “Finding a match for a joke

and a match for a style,” Bellos writes, “are both instances of a more

general ability that may best be called a pattern-matching skill.”

Translation, Bellos proposes in a dryly explosive statement, rather than

providing a substitute instead “provides for some community an

acceptable match for an utterance made in a foreign tongue.” What makes a

match acceptable will vary according to that community’s idea of what

aspects of an utterance need to be matched by its translation. After

all, “no translation can be expected to be like its source in more than a

few selected ways.” So a translation can’t be right or wrong “in the

manner of a school quiz or a bank statement. A translation is more like a

portrait in oils.” In a translation, as any art form, the search is for

an equivalent sign.

And for the inhabitants of London or Los Angeles, this dismantling of

the myths around translation has peculiar implications. As Bellos points

out, those born as English speakers are now a minority of English

speakers: most speak it as a second language. English is the world’s

biggest interlanguage.

So two futures, I think, can be drawn from this dazzlingly inventive

book, and they are gratifyingly large. The first is for every English

speaker. Google Translate, no doubt about it, is a device with an

exuberant future. It’s already so successful because, unlike previous

machine translators, but like other Google inventions, it’s a pattern

recognition machine. It analyzes the corpus of existing translations,

and finds statistical matches. The implications of this still haven’t, I

think, been adequately explored: from world newspapers, to world

novels. . . . And it made me imagine a second prospect — confined to a

smaller, hypersubset of English speakers, the novelists. I am an

English-speaking novelist, after all. There was no reason, I argued to

myself, that translations of fiction couldn’t be made far more

extensively in and out of languages that are not a work’s original. Yes,

I started to cherish a future history of the novel that would be

recklessly international. In other words: there’d be nothing wrong, I

kept thinking, with making translation more joyful.

Adam Thirlwell’s most recent novel is “The Escape.”

Monday, 18 June 2012

(EN) Antony Beevor in defence of history

Antony Beevor in defence of history

The

teaching of history provides much more than the practical skills which

underpin the study of politics and society, it also gives children a

vital understanding of their place in the world, argues Antony Beevor

Also in tomorrow's Guardian Review: Philip Pullman, Hilary Mantel, Jeremy Paxman and others each choose a news photo that sums up the decade; William Boyd on an episode from Any Human Heart, soon to be on TV; an interview with CJ Sansom, author of Tudor murder mysteries; Mary Beard's review of Neil MacGregor's World in 100 Objects; and much more

Also in tomorrow's Guardian Review: Philip Pullman, Hilary Mantel, Jeremy Paxman and others each choose a news photo that sums up the decade; William Boyd on an episode from Any Human Heart, soon to be on TV; an interview with CJ Sansom, author of Tudor murder mysteries; Mary Beard's review of Neil MacGregor's World in 100 Objects; and much more

Adrift in history ... a detail of

Napoleon on Horseback at the St Bernard Pass by Jacques-Louis David.

Photograph: Archivo Iconografico

Is history

as good as finished? Our school system seems to think so. Often it

seems that the teaching of history is treated by the educational

establishment as the rough equivalent of the teaching of dead languages:

an unnecessary luxury of a bygone age, and something the modern world

no longer requires. In the most recent debates about the national

curriculum, history has been granted the status of an "inessential

subject". This is a grave and myopic mistake.

At a purely

practical level, history is important because it provides the basic

skills needed for students to go further in sociology, politics,

international relations and economics. History is also an ideal

discipline for almost all careers in the law, the civil service and the

private sector. This is because the history essay teaches students to

research and assess material, to marshal facts and develop arguments,

and to arrive at logical conclusions. The composition of a such an essay

trains young people to write reports and prepare a presentation. These

are skills that employers say graduates lack.

History is also

necessary because it helps to explain current events. How did western

culture and western capitalism come to dominate the world? How do

cultures rise and how do they fall? We need to know – because otherwise

we will not understand the consequences of the rise of China, India and

Brazil, the weakening of the United States, the political and economic

decline of Europe. History will not give us the answers, but it will

certainly help to focus our questions and our understanding of the

forces at work in the world today.

Of course history is easily

manipulated – though that makes it even more important for us to know

what actually happened. We need a knowledge of history to spot the

delusions of leaders making false parallels, such as President Bush

comparing 9/11 to Pearl Harbor, or Tony Blair talking of Saddam Hussein

as another Hitler. The media, too, are responsible for sloppy

comparisons that are highly misleading. As voters, and as citizens, we

have to be able to see through these dangerous distortions.

Teachers

who are responsible for the subject have little time to devote to these

questions. Year by year, the hours devoted to the subject have been

whittled away. Along with Albania and Iceland, Britain is now one of the

few countries in Europe not to require the study of history after the

age of 14. Worse, the subject is taught in exam-oriented modules – or,

to put it differently, in totally unconnected bubbles of specialist

knowledge.

How can a child grasp developments without a timeline? A

decade appears to them a very long time, so a century, let alone a

millennium, is way beyond their imagination. Some sort of understanding

of key events in Britain and the world is thus essential to provide a

context and a chronological framework. A friend who taught the history

of medicine to graduate doctors told me that she could no longer use

terms such as "Napoleonic" or "Victorian". Her highly qualified students

had heard of Napoleon and Queen Victoria, but most had no idea in which

centuries they had lived.

Besides, history is – or should be –

interesting. Though once (not inaccurately) described as "just one

damned thing after another", the chain of cause and effect is

fascinating, as are the details. Shying away from this, many teachers

who lack historical training themselves are naturally defensive, fearing

that the subject may be boring to their pupils. Knowing that their only

contact with history is through films or television dramas, teachers

are tempted to compound the process, even using programmes such as Blackadder

to teach the first world war. In an increasingly post-literate society

where the moving image is king, the dramatic fictionalisation of history

may soon become the predominant form.

Already, television

and film have influenced more schools and pupils to choose "Hitler and

the Henries" for their exams, simply because they are more comfortable

with something they recognise. But as Simon Schama rightly argued in the Guardian on Tuesday,

there are many other periods and events that are both exciting and

hugely significant. Much more of a story-telling approach is needed to

grip the imagination of the young. This should not be difficult. Ever

since Edward Gibbon in the 18th century, British historians have usually

adopted a narrative drive and broad sweep, in sharp contrast to the

often analytic approach in the rest of Europe.

Critics may say

that British history is far too parochial and makes immigrants and those

from other cultures feel excluded. But if the subject is taught well,

it should show all young people how this country, since the very

earliest times, has absorbed successive waves of migration. Teaching the

history of the British empire links in with that of the world: for

better and for worse, the empire made us what we are, forming our

national identity. A country that does not understand its own history is

unlikely to respect that of others.

I would never argue that

historians or history teachers have a moral role. Their main obligation

is to understand the mentality of the time and to pass on that

understanding: it is not to apply 21st-century values in retrospect. Nor

should they simplify for moral effect. It is absolutely right to convey

the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade, but the role of African

leaders themselves in promoting slavery must also be explained. So must

the fact that the eastern slave trade, mainly to the Arabian

peninsula, was older and more lethal. Certainly it led to the death of

more victims in peculiarly horrible circumstances.

Of course

history should never be used to inculcate virtuous citizenship. Yet it

offers the richest imaginable source of moral examples and moral

dilemmas, which are themselves the essence of great fiction, great

drama, and life itself. Without an understanding of history, we are

politically, culturally and socially impoverished. If we sacrifice

history to economic pressures or to budget cuts, we will lose a part of

who we are.

Wednesday, 13 June 2012

(EN) London and The Old Bailey without qualified professionals

Court cases hampered by translation failures

Up to 50 court cases a day were delayed or postponed because of failures by a translation contractor to provide an adequate service,

New powers to charge fine dodgers

By

Tom Whitehead, Security Editor

5:31PM BST 24 May 2012

The Ministry of Justice is monitoring the performance of Applied Language

Solutions (ALS) after it failed to meet targets.

Judges and court users have complained of delays and even failures by

interpreters to turn up since ALS took on the £300 million five-year

contract in February.

Figures yesterday showed that the company only fulfilled 81 per cent of the

23,234 requests for its services made between February and April this year.

Complaints have included failures to show, poor language skills by the

interpreters or no one being available.

Interpreters said they had boycotted the firm in reaction to low rates of pay,

claiming that led to a struggle by ALS to recruit translators, and prompting

the use of untrained people in courts.

Between January 30 and April 30, there were 2,232 complaints about the

translator service.

The figures showed that by April, the success rate for ALS in fulfilling requests had risen to 90 per cent, but that was still short of the 98 per cent target set by the Ministry of Justice.

An MoJ spokesman said: "We continue to monitor performance on a daily basis.

"However, the contract is now delivering an effective service and we expect to see improvements in the coming months."

The spokesman added: "We have now seen a significant and sustained improvement in performance.

"There are now only a tiny handful of cases each day when an interpreter job is unfilled.

"Disruption to court business and complaints have reduced substantially and close to 3,000 interpreters are now working under this contract.

"We continue to monitor the improvement on a daily basis."

The MoJ report also revealed the scale of the impact immigration has had on the courts system.

A total of 26,059 requests for translation services, covering 142 different languages, were made by the courts during the three months of February to April.

That is the equivalent of 290 a day, with criminal courts accounting for 53 per cent of them.

Four languages made up more than a third of all requests: Polish, Romanian, Urdu and Lithuanian.

The figures showed that by April, the success rate for ALS in fulfilling requests had risen to 90 per cent, but that was still short of the 98 per cent target set by the Ministry of Justice.

An MoJ spokesman said: "We continue to monitor performance on a daily basis.

"However, the contract is now delivering an effective service and we expect to see improvements in the coming months."

The spokesman added: "We have now seen a significant and sustained improvement in performance.

"There are now only a tiny handful of cases each day when an interpreter job is unfilled.

"Disruption to court business and complaints have reduced substantially and close to 3,000 interpreters are now working under this contract.

"We continue to monitor the improvement on a daily basis."

The MoJ report also revealed the scale of the impact immigration has had on the courts system.

A total of 26,059 requests for translation services, covering 142 different languages, were made by the courts during the three months of February to April.

That is the equivalent of 290 a day, with criminal courts accounting for 53 per cent of them.

Four languages made up more than a third of all requests: Polish, Romanian, Urdu and Lithuanian.

Thursday, 7 June 2012

(EN) Welcome to nowhere

Welcome to nowhere

If

you struggle to find Transnistria or Somaliland in an atlas, there's a

reason: they don't officially exist. But can you holiday there? Gwyn

Topham reports

|

| Cold war ... Simon Reeve in Nagorno-Karabakh, whose borders are lined with Armenian snipers |

For many travellers, a place might as well not exist if it isn't

listed in the local Lonely Planet. But there is another level of

non-existence: a whole swath of regions, conflict areas and breakaway

states, off the political map, unrecognised by the international

community, where people stubbornly continue to live. These are the sort

of places Simon Reeve has chosen to visit.

Welcome to

Transnistria, a self-proclaimed state in a Soviet time-warp on the edge

of Moldova; to Somaliland, struggling for independence and international

recognition, where a doctor doubles as the foreign minister; to

Nagorno-Karabakh, whose borders are lined with Armenian snipers as Azeri

refugees vow to reclaim their land.

These destinations feature in the latest series of the BBC's Holidays in the Danger Zone, programmes described as "current-affairs travelogues" where gunmen and poverty are recurring themes. They may not be high on many tourist itineraries, but Reeve says many of these places can - perhaps should - be visited.

"Up until recently, going to Peru and Thailand was exotic, on the edge of exploration - now you go there on your gap year as an 18-year-old, and there's a Boots on Ko Samui. So if you want to push the boundaries a little bit more, where do you go?" In Reeve's case, breakaway republics in the Caucuses and disputed territories in Africa and Asia.

There have been some fabulous traveller's tales and encounters en route - from buying fake passports and drinking snake's blood to finding a field full of abandoned missiles. Having a camera was a double-edged sword, Reeve says; it got him incredible access in some places, but also made others suspicious. He describes the trips as a bit like going away with a few mates and making a video diary - except few have such surreal moments as suddenly being in the lift chatting with one president, or going fishing with another.

But could anyone, without BBC credentials, really just go there? "Yes, absolutely! Lots of places you can just wander in. You'd have to be the sort of person who doesn't need a Thomson holiday rep to show you around, sure. But you'd also find your money went a lot further."

And, he says, the scenery is pretty special. "Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, the central highlands of Taiwan - they're stunning, the sort of stuff that makes you go - [mimes jaw dropping]."

It should be stressed that, having been to Mogadishu en route to Somaliland - "You're either fine or you're killed" - Reeve may not have the same conception of a dodgy place as the rest of us. He is also the veteran of trips through central Asia for a previous series, Meet the Stans, and has paddled through Borneo looking for Al-Qaida training camps while researching his book on Bin Laden, The New Jackals - published in 1998 and which came to belated international attention after September 11.

Reeve, who

started his career in the postroom at the Sunday Times and never got on

a plane until he was 19, says: "I love the fact that I've been able to

go to the last remaining outposts of the Soviet empire, the Stalinist

empire, remaining on earth, in Transnistria. And Somaliland was quite

inspirational ... what the locals have achieved there is extraordinary."

Reeve, who

started his career in the postroom at the Sunday Times and never got on

a plane until he was 19, says: "I love the fact that I've been able to

go to the last remaining outposts of the Soviet empire, the Stalinist

empire, remaining on earth, in Transnistria. And Somaliland was quite

inspirational ... what the locals have achieved there is extraordinary."

He watched Michael Palin when he was younger, "like everyone else", and now clearly fancies a shot at his job. "Wouldn't it be fantastic?" he sighs, staring dreamily into the distance.

Perhaps he could already replicate the Palin effect by opening new areas to travellers. "I love the idea that in 10 years Somaliland may have international recognition, and people can go and see its fantastic beaches. An acre wide, sand between your toes. I can see that happening one day, yeah."

Reeve's tourist guide to places that don't exist

Somaliland

"There are decent hotels, and not just by my standard of sleeping in a shithole. They'll arrange a guide and transportation for you. Number-one attraction is the people - I know that sounds corny, but they are inspirational. That aside, there's the rock paintings, the finest Neolithic paintings in the whole of Africa. They've only recently been discovered by a French archaeologist and no tourists go there to see them. So for people who are lucky enough to go, you're seeing a totally untouristy sight. You're driving through the African bush and you get to a village, and you go and see these paintings that are thousands and thousands of years old, and you just look at them in wonder.

"Even on the way to them you'll see pre-Islamic burial sites, and you just realise you're travelling through an ancient land which we really know nothing about now. The views are fantastic, and you've got the sea: coral, mangrove, paradise islands just off the coast."

· Fly with Daallo airlines from Kenya or Djibouti.

Taiwan

"A fantastic tourist destination so long as there's no war with China, which admittedly will cause a few problems ... Because the Taiwanese saw themselves as China's natural rulers, they have been obsessed with preserving the heritage. The Chinese have knocked a lot of things down; if you travel round China, you're seeing megalopolises. In Taiwan you'll see the authentic temples that have disappeared from the mainland. The landscape is lush, and you've got history and architecture there as well."

· KLM fly to Taipei via Amsterdam and Bangkok.

Georgia's breakaway republics

"Georgia does have a lot of tourist sights: mountains, monasteries, skiing in winter, lakeside beaches in the summer. It's the birthplace of Stalin; you've got Stalin's museum, where you can go and do what I did and sit on his personal toilet when the guards aren't looking, and imagine Stalin's bottom gracing this seat of power and privilege.

"In South Ossetia admittedly, there isn't an awful lot to see. But you will get a South Ossetian stamp in your passport. And some ex-Soviet stuff - well, a lot of it is almost still Soviet.

"Ajaria has been brought back into the Georgian fold. There are health resorts on the Black Sea; it was a destination for Soviet holidaymakers, and has a great climate in the summer. It's not going to be Club Tropicana, right?

"I'd love to tell you more about Abkhazia but the day before we were due to go, they said we're not going to let you in because we've had some internal warfare in our government. But I'm told it's beautiful. Some say it was the home of the Golden Fleece, and the original garden of Eden."

· Fly to Tblisi via Amsterdam with bmi and KLM. An overnight train to Ajaria costs about £6. South Ossetia and Abkhasia are best visited from Russia.

Transnistria

"You could probably get here for a long weekend. From Chisinau, the Moldovan capital, you can just get a bus or a taxi to Transnistria for the price of a bag of chips. If you're on the bus, just sit at the back and keep quiet. But even being stopped by the Transnistria immigration officials is going to be a fun experience; if you're the sort of person who's prepared to go there then you want that sort of thing."

· Malev Hungarian Airlines fly to Chisinau via Budapest.

Nagorno-Karabakh

"I would caution about going here because morally the situation is very questionable - although it's a very beautiful place. "

· Entry via Armenia.

· The UK Foreign Office advises against travel to Somaliland, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and advises caution in Transnistria, although tensions have recently eased in Ajaria. In addition, the UK has no diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Reeve's top tips

* In these countries $5 goes a long way.

* If you want to see something, you might find there are "special entrance fees" that will get you in.

* You probably need a visa - but the rules are fairly flexible; you aren't going to Sweden.

· Simon Reeve's new 5-part series, Holidays in the Danger Zone: Places that Don't Exist, begins Wednesday May 4 on BBC2 at 7.30pm.

These destinations feature in the latest series of the BBC's Holidays in the Danger Zone, programmes described as "current-affairs travelogues" where gunmen and poverty are recurring themes. They may not be high on many tourist itineraries, but Reeve says many of these places can - perhaps should - be visited.

"Up until recently, going to Peru and Thailand was exotic, on the edge of exploration - now you go there on your gap year as an 18-year-old, and there's a Boots on Ko Samui. So if you want to push the boundaries a little bit more, where do you go?" In Reeve's case, breakaway republics in the Caucuses and disputed territories in Africa and Asia.

There have been some fabulous traveller's tales and encounters en route - from buying fake passports and drinking snake's blood to finding a field full of abandoned missiles. Having a camera was a double-edged sword, Reeve says; it got him incredible access in some places, but also made others suspicious. He describes the trips as a bit like going away with a few mates and making a video diary - except few have such surreal moments as suddenly being in the lift chatting with one president, or going fishing with another.

But could anyone, without BBC credentials, really just go there? "Yes, absolutely! Lots of places you can just wander in. You'd have to be the sort of person who doesn't need a Thomson holiday rep to show you around, sure. But you'd also find your money went a lot further."

And, he says, the scenery is pretty special. "Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, the central highlands of Taiwan - they're stunning, the sort of stuff that makes you go - [mimes jaw dropping]."

It should be stressed that, having been to Mogadishu en route to Somaliland - "You're either fine or you're killed" - Reeve may not have the same conception of a dodgy place as the rest of us. He is also the veteran of trips through central Asia for a previous series, Meet the Stans, and has paddled through Borneo looking for Al-Qaida training camps while researching his book on Bin Laden, The New Jackals - published in 1998 and which came to belated international attention after September 11.

Reeve, who

started his career in the postroom at the Sunday Times and never got on

a plane until he was 19, says: "I love the fact that I've been able to

go to the last remaining outposts of the Soviet empire, the Stalinist

empire, remaining on earth, in Transnistria. And Somaliland was quite

inspirational ... what the locals have achieved there is extraordinary."

Reeve, who

started his career in the postroom at the Sunday Times and never got on

a plane until he was 19, says: "I love the fact that I've been able to

go to the last remaining outposts of the Soviet empire, the Stalinist

empire, remaining on earth, in Transnistria. And Somaliland was quite

inspirational ... what the locals have achieved there is extraordinary."

He watched Michael Palin when he was younger, "like everyone else", and now clearly fancies a shot at his job. "Wouldn't it be fantastic?" he sighs, staring dreamily into the distance.

Perhaps he could already replicate the Palin effect by opening new areas to travellers. "I love the idea that in 10 years Somaliland may have international recognition, and people can go and see its fantastic beaches. An acre wide, sand between your toes. I can see that happening one day, yeah."

Reeve's tourist guide to places that don't exist

Somaliland

"There are decent hotels, and not just by my standard of sleeping in a shithole. They'll arrange a guide and transportation for you. Number-one attraction is the people - I know that sounds corny, but they are inspirational. That aside, there's the rock paintings, the finest Neolithic paintings in the whole of Africa. They've only recently been discovered by a French archaeologist and no tourists go there to see them. So for people who are lucky enough to go, you're seeing a totally untouristy sight. You're driving through the African bush and you get to a village, and you go and see these paintings that are thousands and thousands of years old, and you just look at them in wonder.

"Even on the way to them you'll see pre-Islamic burial sites, and you just realise you're travelling through an ancient land which we really know nothing about now. The views are fantastic, and you've got the sea: coral, mangrove, paradise islands just off the coast."

· Fly with Daallo airlines from Kenya or Djibouti.

Taiwan

"A fantastic tourist destination so long as there's no war with China, which admittedly will cause a few problems ... Because the Taiwanese saw themselves as China's natural rulers, they have been obsessed with preserving the heritage. The Chinese have knocked a lot of things down; if you travel round China, you're seeing megalopolises. In Taiwan you'll see the authentic temples that have disappeared from the mainland. The landscape is lush, and you've got history and architecture there as well."

· KLM fly to Taipei via Amsterdam and Bangkok.

Georgia's breakaway republics

"Georgia does have a lot of tourist sights: mountains, monasteries, skiing in winter, lakeside beaches in the summer. It's the birthplace of Stalin; you've got Stalin's museum, where you can go and do what I did and sit on his personal toilet when the guards aren't looking, and imagine Stalin's bottom gracing this seat of power and privilege.

"In South Ossetia admittedly, there isn't an awful lot to see. But you will get a South Ossetian stamp in your passport. And some ex-Soviet stuff - well, a lot of it is almost still Soviet.

"Ajaria has been brought back into the Georgian fold. There are health resorts on the Black Sea; it was a destination for Soviet holidaymakers, and has a great climate in the summer. It's not going to be Club Tropicana, right?

"I'd love to tell you more about Abkhazia but the day before we were due to go, they said we're not going to let you in because we've had some internal warfare in our government. But I'm told it's beautiful. Some say it was the home of the Golden Fleece, and the original garden of Eden."

· Fly to Tblisi via Amsterdam with bmi and KLM. An overnight train to Ajaria costs about £6. South Ossetia and Abkhasia are best visited from Russia.

Transnistria

"You could probably get here for a long weekend. From Chisinau, the Moldovan capital, you can just get a bus or a taxi to Transnistria for the price of a bag of chips. If you're on the bus, just sit at the back and keep quiet. But even being stopped by the Transnistria immigration officials is going to be a fun experience; if you're the sort of person who's prepared to go there then you want that sort of thing."

· Malev Hungarian Airlines fly to Chisinau via Budapest.

Nagorno-Karabakh

"I would caution about going here because morally the situation is very questionable - although it's a very beautiful place. "

· Entry via Armenia.

· The UK Foreign Office advises against travel to Somaliland, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and advises caution in Transnistria, although tensions have recently eased in Ajaria. In addition, the UK has no diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Reeve's top tips

* In these countries $5 goes a long way.

* If you want to see something, you might find there are "special entrance fees" that will get you in.

* You probably need a visa - but the rules are fairly flexible; you aren't going to Sweden.

· Simon Reeve's new 5-part series, Holidays in the Danger Zone: Places that Don't Exist, begins Wednesday May 4 on BBC2 at 7.30pm.

Wednesday, 6 June 2012

(EN) Ray Bradbury

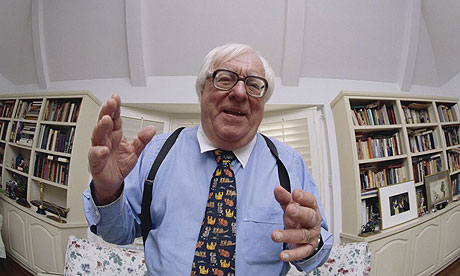

Ray Bradbury, writer who captivated a generation of sci-fi fans, dies at 91

Giant of science fiction writing fueled renewed interest in futurist literature with Fahrenheit 451 among scores of other works

|

| Ray Bradbury, pictured here in an undated photo |

Despite the exhortations of Mr Electrico, a carnival sideshow act with an electrified sword who demanded that a 12-year-old Ray Bradbury "live forever!", one of the most well-loved and highly-regarded modern writers of the fantastic has died.

At 91, though, he left a body of work that might just fulfil the prophecy of that showman in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1932.

One of the most widely read authors of his generation, Bradbury published a string of titles in the early 1950s – The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 – that captured the political fears of a generation and fueled renewed interest in futurist literature.

His most famous work, Fahrenheit 451, named for a proposed temperature at which books combust, imagines a golden age of war and ignorance in which "firemen" burn books instead of putting out fires. Ever since its publication in 1953, the book has been a mainstay of high school English syllabuses.

The news of his death, in southern California, was broken by the sci-fi news website Io9. It quoted his grandson, Danny Karapetian, as saying: "If I had to make any statement, it would be how much I love and miss him, and I look forward to hearing everyone's memories about him. He influenced so many artists, writers, teachers, scientists, and it's always really touching and comforting to hear their stories. Your stories.

"His legacy lives on in his monumental body of books, film, television and theater, but more importantly, in the minds and hearts of anyone who read him, because to read him was to know him. He was the biggest kid I know."

It was Bradbury's encounter at that Labor Day carnival in his home town that set him on the path of becoming a writer, and laid the groundwork for his unique brand of sometimes creepy, sometimes folksy, often slyly subversive fantastical Americana of whispering winds, sinister circuses, fretting about modern life and how humanity copes – or not – with relocating to distant worlds.

After being told by Mr Electrico that he was the reincarnation of the showman's friend who died in France in the Great War, Bradbury ruminated on his website in 2001: "Why did he say that? I don't know. Was there something in my eagerness, my passion for life, my being ready for some sort of new activity? I don't know the answer to that. All I know is that he said, "Live forever" and gave me a future and in doing so, gave me a past many years before, when his friend died in France.

"Leaving the carnival grounds that day I stood by the carousel and watched the horses go round and round to the music of Beautiful Ohio. Standing there, the tears poured down my face, for I felt that something strange and wonderful had happened to me because of my encounter with Mr Electrico.

"I went home and the next day traveled to Arizona with my folks. When we arrived there a few days later I began to write, full-time. I have written every single day of my life since that day 69 years ago."

Bradbury was born in 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, moving with his family to Los Angeles as a teenager. His first collection of short stories, Dark Carnival, was published in 1947. His best known books were published in the early 1950s. He has a star on the Hollywood walk of fame.

In addition to novels, Bradbury wrote screenplays and scripts for TV shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

In 1954, Bradbury received the National Institute of Arts and Letters Award. He was awarded a National Medal of Art by President George W Bush in 2004. He received the O Henry Prize twice and a National Book Foundation medal. He won an Emmy for scripting the Halloween Tree for television.

Bradbury published an essay last week in the New Yorker about what inspired him to write fiction.

He wrote: "I memorized all of John Carter and Tarzan, and sat on my grandparents' front lawn repeating the stories to anyone who would sit and listen. I would go out to that lawn on summer nights and reach up to the red light of Mars and say, 'Take me home!'

"I yearned to fly away and land there in the strange dusts that blew over dead-sea bottoms toward the ancient cities."

Karapetian noted a particular line written by his grandfather about death. He told Io9: "If you're looking for any single passage to remember him by, I just picked up my copy of The Illustrated Man, my favorite of his books. The introduction is entitled 'Dancing, So As Not to Be Dead,' and there are some great lines about death. My favorite:

"My tunes and numbers are here. They have filled my years, the years when I refused to die. And in order to do that I wrote, I wrote, I wrote, at noon or 3am.

"So as not to be dead.'"

• This article was amended on 6 June 2012. The original erroneously described how, in Fahrenheit 451, "firefighters" burn books instead of putting out fires. This has been corrected to say: "firemen".

At 91, though, he left a body of work that might just fulfil the prophecy of that showman in Waukegan, Illinois, in 1932.

One of the most widely read authors of his generation, Bradbury published a string of titles in the early 1950s – The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man and Fahrenheit 451 – that captured the political fears of a generation and fueled renewed interest in futurist literature.

His most famous work, Fahrenheit 451, named for a proposed temperature at which books combust, imagines a golden age of war and ignorance in which "firemen" burn books instead of putting out fires. Ever since its publication in 1953, the book has been a mainstay of high school English syllabuses.

The news of his death, in southern California, was broken by the sci-fi news website Io9. It quoted his grandson, Danny Karapetian, as saying: "If I had to make any statement, it would be how much I love and miss him, and I look forward to hearing everyone's memories about him. He influenced so many artists, writers, teachers, scientists, and it's always really touching and comforting to hear their stories. Your stories.

"His legacy lives on in his monumental body of books, film, television and theater, but more importantly, in the minds and hearts of anyone who read him, because to read him was to know him. He was the biggest kid I know."

It was Bradbury's encounter at that Labor Day carnival in his home town that set him on the path of becoming a writer, and laid the groundwork for his unique brand of sometimes creepy, sometimes folksy, often slyly subversive fantastical Americana of whispering winds, sinister circuses, fretting about modern life and how humanity copes – or not – with relocating to distant worlds.

After being told by Mr Electrico that he was the reincarnation of the showman's friend who died in France in the Great War, Bradbury ruminated on his website in 2001: "Why did he say that? I don't know. Was there something in my eagerness, my passion for life, my being ready for some sort of new activity? I don't know the answer to that. All I know is that he said, "Live forever" and gave me a future and in doing so, gave me a past many years before, when his friend died in France.

"Leaving the carnival grounds that day I stood by the carousel and watched the horses go round and round to the music of Beautiful Ohio. Standing there, the tears poured down my face, for I felt that something strange and wonderful had happened to me because of my encounter with Mr Electrico.

"I went home and the next day traveled to Arizona with my folks. When we arrived there a few days later I began to write, full-time. I have written every single day of my life since that day 69 years ago."

Bradbury was born in 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, moving with his family to Los Angeles as a teenager. His first collection of short stories, Dark Carnival, was published in 1947. His best known books were published in the early 1950s. He has a star on the Hollywood walk of fame.

In addition to novels, Bradbury wrote screenplays and scripts for TV shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

In 1954, Bradbury received the National Institute of Arts and Letters Award. He was awarded a National Medal of Art by President George W Bush in 2004. He received the O Henry Prize twice and a National Book Foundation medal. He won an Emmy for scripting the Halloween Tree for television.

Bradbury published an essay last week in the New Yorker about what inspired him to write fiction.

He wrote: "I memorized all of John Carter and Tarzan, and sat on my grandparents' front lawn repeating the stories to anyone who would sit and listen. I would go out to that lawn on summer nights and reach up to the red light of Mars and say, 'Take me home!'

"I yearned to fly away and land there in the strange dusts that blew over dead-sea bottoms toward the ancient cities."

Karapetian noted a particular line written by his grandfather about death. He told Io9: "If you're looking for any single passage to remember him by, I just picked up my copy of The Illustrated Man, my favorite of his books. The introduction is entitled 'Dancing, So As Not to Be Dead,' and there are some great lines about death. My favorite:

"My tunes and numbers are here. They have filled my years, the years when I refused to die. And in order to do that I wrote, I wrote, I wrote, at noon or 3am.

"So as not to be dead.'"

• This article was amended on 6 June 2012. The original erroneously described how, in Fahrenheit 451, "firefighters" burn books instead of putting out fires. This has been corrected to say: "firemen".

(EN) Transit of Venus

Transit of Venus captures the imagination of a worldwide audience

This year's transit of Venus was an international social event, with millions in the UK also watching a BBC Horizon special

At 5:45am (BST) on Tuesday morning, the clouds above Blackheath in

London parted and the assembled group of amateur astronomers quickly

pointed their telescopes at the Sun. A well-ordered queue of around 100

people went in for a close look at the black disc of Venus

sliding across the face of our nearest star. The planet had been

transiting for the previous six hours and these were the last few

minutes. By 5:50am it was all over.

"This was a chance to see the mechanism of the heavens in action in a way that you really don't see very often," said Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Greenwich Observatory in London, who helped organise a public viewing of the transit of Venus in Blackheath with the local Flamsteed Astronomical Society.

"And it was a chance to do something as a community. Even when we thought we weren't going to see it, when the clouds were resolutely there, there was a great sense of everybody out there making an effort together. Even if we hadn't seen it, we would have felt it was worth getting up at four in the morning. So, just to catch it literally minutes before it was over was a fantastic bonus."

Last night's transit of Venus was an international social event. Tens of thousands of words and scores of graphics on dozens of websites and in newspapers and magazines had prepared the ground for people around the world to take part in viewing this once-in-a-lifetime event.

Transits of Venus occur in pairs - the last one happened in 2004 and the next pair will not appear until 2117 and 2125. Around the world, the buildup to take part in something so rare was palpable: people tweeted their plans to watch the transit and organised themselves into local groups, they advised each other about the safest ways to take part and quizzed scientists about the things transits can tell us about exoplanets and other heavenly mysteries.

On Tuesday night around 2.4m people in the UK tuned into BBC2 to watch a Horizon special on the science of the transit - a respectable audience for a science programme up against the live launch of Big Brother on Channel 5 (which had 2.7m viewers). A further 1.7m people were watching ITV at the time and 1.4m people were watching Channel 4.

As soon as the transit began at 11pm (BST) on Tuesday night, webcams from Nasa (and a myriad other places) showed live progress and Twitter and Facebook buzzed with newly taken pictures of the event as it unfolded.

Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society, who managed to glimpse the transit from a windswept, cloud-covered hill in the Cotswolds, said that events such as the transit were powerful levers for creating interest in astronomy. "The vast majority of those people aren't going to go on to become research scientists, but one or two might have been adolescents who were wondering about science and perhaps this will spur them on."

Each of the transits in the past few centuries has similarly caught the public's imagination, said Kukula. "It's always been a bellwether of what the latest astronomical technology can do. In the 19th century, photography was just on the scene; in the 21st century, it's digital imaging and then the ease with which these can be distributed on the internet. We saw a little bit of that in 2004 but much more in 2012. The other thing is that we can take pictures of it not just from the Earth but from space as well and that's where some of the most spectacular images have come from."

Massey said the technology would continue to improve. Who knows, he added, perhaps amateur astronomers will routinely control telescopes in space by 2117 and professional scientific missions might see people flying ever closer to the Sun itself.

"I was up at 11pm last night to watch it start from the internet," said Kukula. "You can watch it live, you can watch it from the other side of the world, how cool is that? Captain Cook would have given his right arm to do that."

"This was a chance to see the mechanism of the heavens in action in a way that you really don't see very often," said Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Greenwich Observatory in London, who helped organise a public viewing of the transit of Venus in Blackheath with the local Flamsteed Astronomical Society.

"And it was a chance to do something as a community. Even when we thought we weren't going to see it, when the clouds were resolutely there, there was a great sense of everybody out there making an effort together. Even if we hadn't seen it, we would have felt it was worth getting up at four in the morning. So, just to catch it literally minutes before it was over was a fantastic bonus."

Last night's transit of Venus was an international social event. Tens of thousands of words and scores of graphics on dozens of websites and in newspapers and magazines had prepared the ground for people around the world to take part in viewing this once-in-a-lifetime event.

Transits of Venus occur in pairs - the last one happened in 2004 and the next pair will not appear until 2117 and 2125. Around the world, the buildup to take part in something so rare was palpable: people tweeted their plans to watch the transit and organised themselves into local groups, they advised each other about the safest ways to take part and quizzed scientists about the things transits can tell us about exoplanets and other heavenly mysteries.

On Tuesday night around 2.4m people in the UK tuned into BBC2 to watch a Horizon special on the science of the transit - a respectable audience for a science programme up against the live launch of Big Brother on Channel 5 (which had 2.7m viewers). A further 1.7m people were watching ITV at the time and 1.4m people were watching Channel 4.

As soon as the transit began at 11pm (BST) on Tuesday night, webcams from Nasa (and a myriad other places) showed live progress and Twitter and Facebook buzzed with newly taken pictures of the event as it unfolded.

Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society, who managed to glimpse the transit from a windswept, cloud-covered hill in the Cotswolds, said that events such as the transit were powerful levers for creating interest in astronomy. "The vast majority of those people aren't going to go on to become research scientists, but one or two might have been adolescents who were wondering about science and perhaps this will spur them on."

Each of the transits in the past few centuries has similarly caught the public's imagination, said Kukula. "It's always been a bellwether of what the latest astronomical technology can do. In the 19th century, photography was just on the scene; in the 21st century, it's digital imaging and then the ease with which these can be distributed on the internet. We saw a little bit of that in 2004 but much more in 2012. The other thing is that we can take pictures of it not just from the Earth but from space as well and that's where some of the most spectacular images have come from."

Massey said the technology would continue to improve. Who knows, he added, perhaps amateur astronomers will routinely control telescopes in space by 2117 and professional scientific missions might see people flying ever closer to the Sun itself.

"I was up at 11pm last night to watch it start from the internet," said Kukula. "You can watch it live, you can watch it from the other side of the world, how cool is that? Captain Cook would have given his right arm to do that."

Monday, 4 June 2012

(EN) London 1942

London Calling: A Countercultural History of London Since 1945 by Barry Miles – review

Barry Miles chronicles the capital's postwar counterculture with wit, style and a refreshing lack of nostalgia

Old Compton Street, Soho, 1959: Miles's book evokes a now vanished city. Photograph: Dezo Hoffmann/Rex Features

Noting an influx of film people and the loss of cheap cafes for

artists, guidebook writer Stanley Jackson declared bohemianism in Soho

all but dead as long ago as 1946. Barry Miles, co-founder of 60s

underground newspaper International Times, is alive to the

dangers of making such fateful pronouncements. All the same, his hugely

enjoyable survey of London's cultural underbelly has the feel of a

requiem.

With Francis Bacon's beloved Colony Room gone, and the Groucho

Club owned by a private equity firm, the capital's truly countercultural

days are firmly behind it. Miles is tremendous at evoking a now

vanished city of coffee bars and out-of-hours drinking dens, a sordidly

romantic metropolis where days could be idled away in a fog of Craven

"A" smoke alongside impecunious poets, French prostitutes and bearded

folk musicians. The internet, Miles reasons, has eroded the importance

of place and is killing off the avant-garde by making any activity

(however outrageous) instantly accessible.

Pure nostalgia, though, is kept firmly in check by eye-opening details of Withnail and I-esque squalor, the greatest furnished from the author's own memories. (A description of the novelist Alexander Trocchi's Holland Park penthouse littered with used syringes makes for distinctly queasy reading.) The book ranges from the postwar Fitzrovia of Julian Maclaren-Ross to the Young British Artists in Shoreditch around the millennium. But, inevitably, it is at its most assured – and original – when covering the 1960s.

One thing Miles conveys well is the degree to which a deeply antagonistic establishment was a necessary evil in all of this. Police raids on nightclubs, bookshops and galleries stud the narrative like cloves in a ham. Even the Park Square Mews home of Radio 1's John Peel was seemingly not immune from the attention of the boys in blue. The constant harassment of Le Deuce, the pioneering gay disco on D'Arblay Street frequented by Derek Jarman, had fatal consequences for the club's tropical fish: every time it was raided, the clientele tossed their pep pills into the tank beside the dance floor, poisoning the fish in the process.

Pure nostalgia, though, is kept firmly in check by eye-opening details of Withnail and I-esque squalor, the greatest furnished from the author's own memories. (A description of the novelist Alexander Trocchi's Holland Park penthouse littered with used syringes makes for distinctly queasy reading.) The book ranges from the postwar Fitzrovia of Julian Maclaren-Ross to the Young British Artists in Shoreditch around the millennium. But, inevitably, it is at its most assured – and original – when covering the 1960s.

One thing Miles conveys well is the degree to which a deeply antagonistic establishment was a necessary evil in all of this. Police raids on nightclubs, bookshops and galleries stud the narrative like cloves in a ham. Even the Park Square Mews home of Radio 1's John Peel was seemingly not immune from the attention of the boys in blue. The constant harassment of Le Deuce, the pioneering gay disco on D'Arblay Street frequented by Derek Jarman, had fatal consequences for the club's tropical fish: every time it was raided, the clientele tossed their pep pills into the tank beside the dance floor, poisoning the fish in the process.

Friday, 1 June 2012

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

(EN) Preserver of Nearly Extinct Languages

Kenneth L. Hale, 67, Preserver of Nearly Extinct Languages

By WOLFGANG SAXON

Published: October 19, 2001

Dr. Kenneth Locke Hale, a master of more than 50 languages and the

keeper of aboriginal tongues in danger of vanishing with their speakers,

died on Oct. 8 at his home in Lexington, Mass. He was 67.

The cause was prostate cancer, said the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he was a professor of linguistics.

Dr. Hale's knack for quickly picking up a language and conversing

in dozens of them earned him an international reputation. His

theoretical interests focused on linguistic universals, prompting him to

learn as many disparate languages as possible and investigate laws or

structures they might have in common.

Dr. Hale's knack for quickly picking up a language and conversing

in dozens of them earned him an international reputation. His

theoretical interests focused on linguistic universals, prompting him to

learn as many disparate languages as possible and investigate laws or

structures they might have in common.

His studies contributed to the continuing quest for a general

theory of the human capacity for language. But he was best known for his

commitment to keep alive the unwritten speech of peoples at risk of

extinction by assimilation or other means.

Dr. Hale learned some of the ancient languages of the American

Indians and the Australian Aborigines, and he saw some of the languages

and their speakers disappear after he had learned them.

Throughout his career he promoted linguistic training for speakers

of languages of indigenous peoples so that they could preserve them and

pass them on to another generation. According to M.I.T., two of his

graduate students, a Hopi and a Navajo, were the first Native Americans

to receive doctorates in linguistics.

''Ken viewed languages as if they were works of art,'' said Dr.

Samuel Jay Keyser, a friend and M.I.T. colleague. ''Every person who

spoke a language was a curator of a masterpiece.''

Another colleague, Dr. Philip Khoury, an M.I.T. dean, said he once

asked Dr. Hale about his ability to speak languages by the dozen. ''The

problem is,'' he quoted Dr. Hale's reply, ''that many of the languages

I've learned are extinct, or close to extinction, and I have no one to

speak them with.''

Kenneth Hale grew up on a ranch in Canelo, Ariz., and attended a

one-room grade school he reached on horseback every morning. Sent on to

school in Sedona, Ariz., he learned Hopi and Jemez from roommates and

figured out how to write languages that had no letters.

''I learned faster by working on more than one language at a

time,'' he recalled later. Since high school, he said, he quickly moved

on to Navajo, O'odam, Papago, Pachuco, Polish and whatever came along,

including eight Australian Aboriginal languages.

As an undergraduate at the University of Arizona he studied

anthropology and Native American languages. He also rode rodeo bulls,

won the university's bull-riding event as a senior and kept the buckle

of his trophy belt for the rest of his life.

After graduating in 1955, he received a master's degree in 1956 and

a doctorate in 1958 in linguistics at Indiana University. He researched

Australian Aboriginal languages on a National Science Foundation grant

for three years and worked at the University of Illinois and the

University of Arizona before moving to M.I.T. in 1967.

He retired from teaching in 1999.

Over the years he trained Walpiri-speaking teachers in Central

Australia and taught linguistics in Arizona for the Navajo Language

Academy. He was involved in a language revitalization project for the

Wampanoag tribe of New England and for the last 15 years visited the

Caribbean coast of Nicaragua to teach linguists in four indigenous

languages.

He was the editor most recently, with Dr. Leanne Hinton, of ''The

Green Book of Language Revitalization,'' published this year. Another

book he recently completed with Dr. Keyser, ''Prolegomena to a Theory of

Argument Structure,'' is to be published by M.I.T. Press.

He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1990.

Dr. Hale is survived by his wife of 46 years, Sara Whitaker Hale;

four sons, Whitaker, of Arlington, Mass., Ian, of Tucson, Caleb, of

Atlanta, and Ezra, of Lexington; and a brother, Stephen F., of Tucson.

Dr. Hale was modest about his polyglot accomplishment. ''It's more

like a musical talent than anything else,'' he told The New York Times

in 1997. ''When I found out I could speak Navajo at the age of 12, I

used to go out every day and sit on a rock and talk Navajo to myself,''

he recalled.

He said he could never learn a language in a classroom, but only

one on one with a person. He said he would start with parts of the body,

common animals and objects, learn nouns, pick up sound systems and

write it all down.

''If it's not a written language, like Nggoth, which is spoken in

Australia,'' he said, ''I make up how to write it. I can learn that in

one or two hours.

''Then I start making complex sentences because the complex

sentences are more regular than the simple ones. Then pretty soon I can

name anything in the world.''

(ES) Detienen en Barcelona a estafadores de traductores

Detienen en Barcelona a los responsables de una empresa por estafar a traductores

Barcelona

|

30/05/2012 - 08:13h

BARCELONA, 30 (EUROPA PRESS)

Los Mossos

d'Esquadra han detenido en Barcelona a un matrimonio de Dosrius

(Barcelona), responsables de una empresa, por presuntamente estafar y

usurpar la identidad de una cuarentena de traductores de toda España, según ha informado la policía catalana.

La investigación se inició en abril cuando una traductora denunció a

la policía que otros traductores autónomos le estaban reclamando el pago

por realizar unos trabajos que ella no había contratado y que para hacerlo alguien había usado su identidad.

El matrimonio imputado era propietario de una empresa de

traducciones, con sede en Barcelona y Tarragona, legalmente constituida,

y que hacía de intermediaria en las traducciones, de manera que buscaba

profesionales de diferentes idiomas para los clientes que contactaban

con ellos.

Los detenidos, Juan Fernando V.F., de 43 años, y

Nuria D.R., de 38, también habrían utilizado identidades falsas de

traductores para encargar los trabajos.

Los detenidos, Juan Fernando V.F., de 43 años, y

Nuria D.R., de 38, también habrían utilizado identidades falsas de

traductores para encargar los trabajos.

Los agentes han

comprobado que los detenidos contactaban a través de páginas web con

diferentes traductores a quienes les ofrecían el trabajo, y éstos la

realizaban, la entregaban y esperaban para cobrarla.

Al

ver que no cobraban por el trabajo, los afectados reclamaban el importe a

la persona que, supuestamente, les había hecho el encargo, y era cuando

descubrían que quien en principio había encargado la traducción, negaba

haberlo hecho o que directamente no existía nadie que coincidiese con

la identidad de quien supuestamente los había contratado.

Por este motivo, a los investigados se les imputa 17 delitos de

usurpación de estado civil, 12 delitos de estafa, 24 faltas de estafa,

dos faltas de coacciones y una falta de amenazas, siendo la cantidad estafada de unos 20.000 euros.

Por las declaraciones de los denunciantes, la estafa se inició hace

unos 10 años, y algunas faltas de estafa ya habían prescrito; muchos de

los afectados no denunciaron los hechos, de lo que se aprovechó el

matrimonio practicando durante años la estafa.

Hasta el

momento, la policía ha contabilizado 39 personas afectadas en Barcelona,

Madrid, Valencia, San Sebastián y Portugal, pero la investigación

apunta a que serían más de 60 los traductores afectados y la cantidad

estafada se podría duplicar.

El Juzgado de Instrucción 26

de Barcelona autorizó el registro simultáneo de las tres sedes de la

empresa, y los Mossos detuvieron al matrimonio el 22 de mayo, que, tras

pasar a disposición judicial, quedó en libertad con cargos.

Tuesday, 29 May 2012

(EN) -Mind your English language-

Mind your English language

While most people accept that language will change with use and time, Sarah Churchwell appears to justify the increasing Americanisation of British English (A neologism thang, innit, 10 May). Noah Webster

may have produced the language that should be known as "American", but

that should not be a reason, as Churchwell seems to imply, for British

English to be altered to the American version. American is characterised

by a plethora of "z"s and a paucity of "u"s, which doesn't even reflect

the way we pronounce many of the affected words. Churchwell seems to

view the French influence on our language as in need of purging. This

has no justification. The French influence is part of the Latin history

of English, as is the impact of Spanish and Italian.

American

terms and spelling are imposed on us via the internet, but television

and lazy journalism are also to blame. Not only is it "new" words, but

creating verbs from nouns is common. Witness her own example

"hierarchize". American versions of words are too common, as in

"bathroom" or "rest room" for toilet, "airplane" for aeroplane, and

"stroller" for buggy. Our English is a rich and varied language – it

needs a strong defence.

John Edwards

Linlithgow, West Lothian

• There's no need for Sarah Churchwell to come back to these shores

and feel the underdog, just because she's an ex-colonial speaker of

English. As such she must know that language, above all, is social. She

condemns "innit" but not "gotten" because, at the moment, the former

usage is English underclass and the latter American mainstream. They

both sound horrible, or OK, according to taste; some even think they are

"cool", democratic, like.

But no amount of genealogical research

citing Shakespeare will effectively whitewash the social meaning of

each. They are abominable not because they sound awful, but because they

represent a depressed and depressing social status in England, on the

one hand, and a bland, thoughtless, faux-classless, sold-by-the-yard

cultural wallpaper from the US, on the other.

Dr James Andrade

St Albans, Hertfordshire

•

What a pity Sarah Churchwell spoils her otherwise well-made case about

the inevitability of language change by a careless remark in her final

paragraph: "From an aesthetic standpoint, 'innit' remains an

abomination." Perhaps this was intended as tongue-in-cheek, but if so, I

doubt it will be interpreted as such by the purists she mentions. And

if not, then Prof Churchwell of all people must know there's no such

thing as intrinsically aesthetically inferior (or superior) language. As

her article demonstrates, it's a matter of personal preference and

prejudice.

Prof Jennifer Jenkins

Chair of Global Englishes, University of Southampton

•

I agree with Sarah Churchwell's attitude to the evolution of English,

but I wish to defend "innit", which she categorises as an abomination.

Most languages have a simple way of designating a question expecting the

answer "yes", eg "n'est ce pas?" or "nich wahr?". English has instead a

bewildering variety of phrases – "didn't he?", "won't they?", "am I

not?" – which have to be crafted for each context, a task which some

non-native speakers find difficult. "Innit" fills the vacant role of a

generic verbal question-mark inviting agreement. I predict that it will

achieve the accolade of inclusion in the OED well before such redundant

items as "grrl".

Herbert Munk

Coventry

•

I can explain to Sarah Churchwell why Scrabblers prefer the word

"amongst" to "among". Using all seven tiles at once gains a bonus of 50

points. To begin a debate, it would be interesting to learn the strength

of feeling amongst players who believe one should always know the

definition of their chosen word.

Mollie Holden

Westgate-on-sea, Kent

•

The ending of "vendor" and "neighbour" is pronounced differently on

both sides of the Atlantic. Not just kowtowing to the French!

Alexander Good

London

Tuesday, 22 May 2012

(EN) -Freedom of speech-

The Azerbaijanis who aren't feeling the Eurovision glow

The EBU, which puts on the kitsch music-fest, is mandated to protect freedom of expression. It should do so in Baku

|

| A policeman detains an opposition activist in Baku … 'The European Broadcasting Union has to decide how it tackles the issue of Azerbaijan's awful human rights record.' |

We are only days away from our annual European dose of kitsch

and glamour delivered wonderfully by the Eurovision song contest, coming

this year to our living rooms from Baku, Azerbaijan on 26 May.

The

warm glow of European togetherness that the show usually generates, at

least for an evening, is one of the things the European Broadcasting

Union, the association of Europe's national public service broadcasters

that puts the contest on stage, loves most about it. The EBU regularly

reminds anyone listening that, particularly at such times of economic

strain in Europe, it's this music-fest, rather than worthy pan-European

political gestures from Brussels or elsewhere, that nudge us toward

loving this continent.

This year, the EBU has an extra challenge regarding Eurovision. It has to decide how it tackles the issue of Azerbaijan's awful human rights record

– not because it necessarily wants to but because activists in Baku and

elsewhere, plus media and some governments in Europe, have forced the

issue into the spotlight.

What has come to light? A terrible record on freedom of expression,

with six journalists in prison on spurious charges; several dozen

opposition political activists also behind bars, according to local

monitors; crackdowns on peaceful protests, most recently on Monday in the centre of Baku;

tight media controls creating a climate of fear in the country; and

physical violence against those saying things the country's

authoritarian government, led by President Ilham Aliyev, does not like.

One of the most recent victims was Idrak Abbasov,

a respected reporter. Last month he was filming forced evictions and

house demolitions by the country's state oil company when the firm's

security officials, along with police, viciously beat him unconscious,

leaving him hospitalised. Investigations into this and other cases are

half-hearted at best.

The EBU's core mandate,

of protecting and promoting the basic rights to freedom of expression,

might suggest it would use the Eurovision occasion to confront

Azerbaijan on its rights record. So far, however, it has very clearly

decided not to do so. This is a setback for journalists and others in

Azerbaijan standing up for freedom of speech, and a stance that the Baku

government can use to legitimise its actions. It's also not great PR

for the EBU itself.

For a media alliance that lives off freedom of

speech to ignore abuses of that freedom on the doorstep of the show's

sparkling seafront venue undercuts the organisation's own credibility.

The EBU has touched gingerly on freedom of expression in Azerbaijan in various statements, and on 2 May held a workshop in Geneva

on these issues aimed at promoting "dialogue" between the Azerbaijan

authorities, local and international pressure groups, and others.

Sadly,

despite EBU pledges of training sessions for journalists in Baku, the

organisation largely gave the senior Azerbaijan officials at the

workshop a free ride on the government's serious human rights abuses.

If

the EBU wants to engage seriously with a country such as Azerbaijan, it

has to get off the fence. Such regimes are often brutal and cunning,

and they need to face international pressure if they are to stop

limiting freedom of expression. In using the EBU's influence, platitudes

about more "dialogue", are not enough.

The EBU and its

members in 56 countries do have influence, and, on paper, high ethical

standards. The body boasts proudly of being "the largest association of

national broadcasters in the world", and in 2010 crafted a new

international declaration – after a conference in Baku, in fact –

"condemn[ing] arrests, harassment and intimidation of journalists" in

the EBU region and "call[ing] on governments to investigate all

instances of violence against journalists and bring to justice those

responsible".

So why so quiet on events on Azerbaijan? On

the six journalists in prison on trumped-up charges? On the journalists

severely beaten in recent months for doing their jobs? And on the

climate of fear that means self-censorship is pervasive?

Human Rights Watch

has, over the last nine months, used meetings and correspondence with

the EBU to explain the severity of conditions in Azerbaijan and the need

to speak out. We have asked the EBU to use its influence to raise

publicly the issue of imprisoned and harassed reporters, and to support

publicly the efforts by Baku's courageous civil society to organise

freedom of speech events in the week before Eurovision.

Such

steps would annoy Azerbaijan and, in our view, this is the reason the

EBU has refused. It argues that Eurovision is apolitical, and that such

issues should be raised on other occasions. But it also admits that, in

the show's 57-year history, it has never faced such a wave of

international concern about the human rights record of the host country

as it has this year.

The EBU still has some time to speak

out – and to get ready to monitor events after Eurovision, when the

international spotlight will have shifted but local journalists and

activists will be at their most vulnerable. Action now by the EBU would

be a good signal, also, on how it will handle future Eurovisions. As one

EBU official noted – what happens if Belarus wins on 26 May?

Saturday, 19 May 2012

(EN) - EL PASO DEL NOROESTE-

Unmapped Northwest Passage proves perilous for ships that stray

Remote sea lanes in Canada's Northwest Passage poorly mapped yet increasingly popular with cruise lines.(Abridged by José V.)

|

Uncharted ... the Northwest Passage from space. Photograph: AP/NASA

Within the space of a week two ships have been involved in accidents in the Northwest Passage, fuelling debate on the environmental risks associated with shipping north of the Arctic

Circle, despite the waters being increasingly ice-free in the summer.

Both accidents were blamed on navigation problems, drawing attention to a

lack of proper charts for the region.

In late August the cruise ship Clipper Adventurer was heading for Kugluktuk, at the entrance to the passage, when it struck a rock not shown on the map, according to the captain of the ship. The Canadian Coast Guard sent an icebreaker to rescue the 110 passengers, taking them to the ship's next port of call. The condition of the ship – still stuck but said to be "stable" by CCG spokeswoman Chantal Guénette – is being closely watched until it can be refloated.