London's economic boom leaves rest of Britain behind

Exclusive: Guardian analysis highlighting regional imbalance raises troubling questions about who is enjoying UK's recovery

London and the

south-east’s share of growth in output has soared since 2007 while every

other region except Scotland has declined. Photograph: Nicholas

Bailey/Rex

During the boom from 1997 to 2006, London and the south-east was responsible for 37% of the UK's growth in output. Since the crash of 2007, however, their share has rocketed to 48%. Every other nation and region – with the exception of Scotland – has suffered relative decline over the same period. The upshot is about a quarter of the population is responsible for half of the UK's growth, leaving the remaining three-quarters of Britons to share the rest.

The research also shows that the UK's highest-earners have become relatively more prosperous after the crash, while many on middle incomes are being squeezed hard. In austerity Britain, the top 20% of earning households are enjoying 37.5% of all Britain's income growth, even after accounting for taxes and benefits.

These findings will embarrass the government, especially as they come shortly before the release of the latest GDP figures on Friday. Ministers are poised to celebrate news that the economy is at last enjoying strong growth, and may even have racked up its best quarter in 13 years. But the Guardian's analysis raises questions about who is enjoying Britain's growth and how sustainable it is, and will fuel the debate over who should bear the burden for an economic crisis that began in the Square Mile.

The Guardian's analysis is based on official measures of gross value added, often used to assess regional and industrial performance, and was conducted by the Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change at Manchester University.

The findings suggests that David Cameron has failed to meet some of his most important promises: on making Britain's economy less lopsided; on ensuring that the pain from its cuts would be fairly shared out; and that banks would lend more to small businesses.

In his first major speech as prime minister, Cameron described Britain as "more and more unbalanced, with our fortunes hitched to a few industries in one corner of the country". Analysis of the statistics shows that regional imbalance has grown sharply since the crash.

The chancellor, George Osborne, has repeatedly claimed that "we're all in this together". But while the highest-earning 20% of households have done well, and the fortunes of the bottom 20% have been boosted by the minimum wage, most of the rest – the so-called squeezed middle – have seen their incomes stretched.

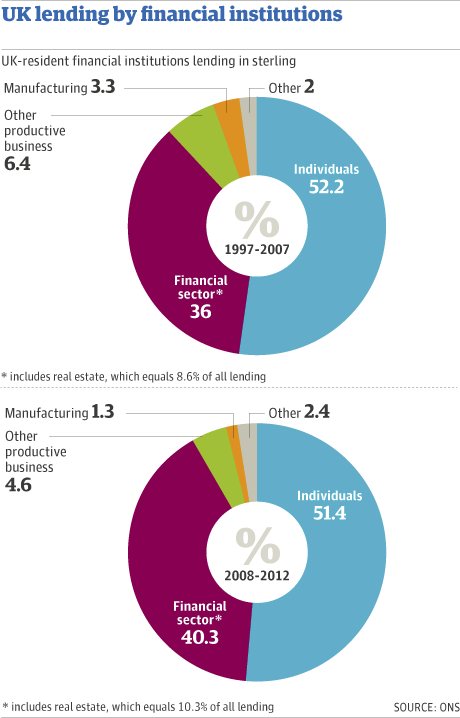

UK lending by financial institutions Photograph: Guardian

Osborne and the business secretary, Vince Cable, have exhorted banks

to lend more to small businesses and to manufacturing. The Guardian's

analysis of the Bank of England's own lending figures shows that the

share of loans to manufacturers and other real businesses have fallen

since the crash. In the decade to 2007, manufacturing and other

"productive businesses" took 9.7% of all bank loans. From 2008 to 2012,

however, that plummeted to just 5.9%. That compares with the 40% of bank

loans to other financial institutions and the 52% of credit extended to

individuals, much of which would have been used for mortgages.

UK lending by financial institutions Photograph: Guardian

Osborne and the business secretary, Vince Cable, have exhorted banks

to lend more to small businesses and to manufacturing. The Guardian's

analysis of the Bank of England's own lending figures shows that the

share of loans to manufacturers and other real businesses have fallen

since the crash. In the decade to 2007, manufacturing and other

"productive businesses" took 9.7% of all bank loans. From 2008 to 2012,

however, that plummeted to just 5.9%. That compares with the 40% of bank

loans to other financial institutions and the 52% of credit extended to

individuals, much of which would have been used for mortgages.In 2010, Cameron described Britain's economy as "unsustainable, unstable, unfair and, frankly, uninspiring", and said that transforming it would be his first priority. Three years on, these figures suggest no such transformation has taken place. Indeed, some of the coalition's policies have been criticised for only Britain's regional and social inqualities.

Infrastructure projects such as the Olympics and the Channel tunnel rail link have seen a huge amount of public spending flowing into London. Last year, the construction skills industry training board forecast that Greater London would receive more economic-development spending than than Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland put together.

This has sat

alongside policies aimed at making credit cheaper and easier, which have

had the effect of making owners of homes and other assets better off.

This month, Nigel Wilson, the chief executive of Legal and General,

described the £375bn quantitative easing programme as "a policy designed

by the rich for the rich".

Share of regional GVA growth Photograph: Guardian

"Since the crash, London and the south-east have continued to pull

away from the rest of the national economy. The wedge between them and

the rest of Britain has been driven in deeper," said Adam Leaver at the

Manchester Business School, and a member of Cresc. The academic team's

work is drawn on the latest GVA (gross value added) figures, which end

in 2011, but there are indications that the divide has only grown since.

Share of regional GVA growth Photograph: Guardian

"Since the crash, London and the south-east have continued to pull

away from the rest of the national economy. The wedge between them and

the rest of Britain has been driven in deeper," said Adam Leaver at the

Manchester Business School, and a member of Cresc. The academic team's

work is drawn on the latest GVA (gross value added) figures, which end

in 2011, but there are indications that the divide has only grown since.This week, a Rightmove survey showed house prices jumping 10% in London in just on